Most club players waste hours memorizing opening lines they will rarely see on the board. At Chess Gaja, many students plateau not because they lack talent, but because they study openings as scripts instead of learning how to think in the positions that arise.

I am Grandmaster Priyadharshan Kannappan, founder of Chess Gaja, and in this article I will show you how to practice chess openings in a way that actually improves your results. You will learn how to focus on principles, choose a compact repertoire, and build a simple training routine that turns your opening study into real points. Whether you’re just starting to study chess openings or improving from intermediate to advanced play, the strategies in this guide work at every level.

Why Understanding Beats Memorization?

Memorizing twenty moves of theory feels satisfying, but it gives a false sense of security. The first time your opponent plays something unexpected on move 8 or 10, you are suddenly on your own, and pure memory no longer helps.

Understanding an opening means you can answer three questions in almost any position:

– What squares matter most here?

– Where should my pieces go to control them?

– What is my opponent trying to do?

When you think in these terms, you can still play strong moves even when the position is new. You stop being a “theory parrot” and become a player who can solve problems over the board.

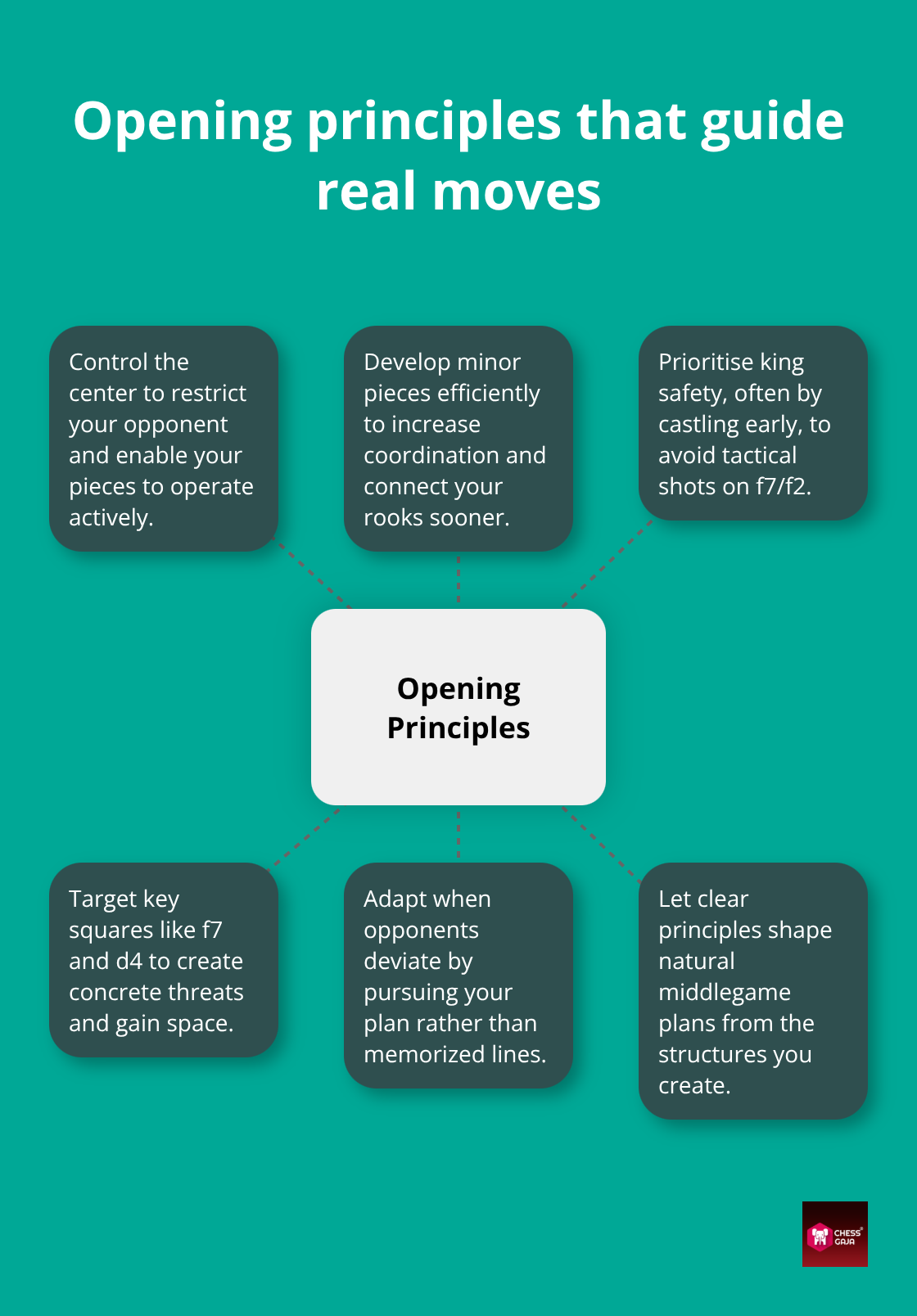

Core Opening Principles in Action

For beginners up to around 1500, you do not need a giant opening tree. You need a solid grasp of a few core principles that repeat in almost every game.

– Control the center: Try to influence the central squares (e4, d4, e5, d5) with your pawns and pieces. Having pieces in the center gives you more options and “space,” which means more safe squares for your pieces and less freedom for your opponent.

– Develop pieces quickly: Bring knights and bishops into the game so they attack useful squares and support your center. Development means getting your pieces off the back rank and into active positions where they participate in the fight.

– Keep your king safe: Usually castle early so your king is protected behind pawns and your rook enters the game.

– Respect pawn structure: Your pawn structure is the pattern of your pawns across the board. Good structures give you clear plans and safe king positions; bad structures create weak pawns and weak squares that your opponent can target.

These ideas are not abstract slogans; they appear in the moves you choose. Let’s look at a simple example in the Italian Game.

Example 1: Italian Game basics

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5.

– With 1.e4 and 2.Nf3, White controls the center (e4, d5, f5) and prepares to castle.

– 3.Bc4 develops the bishop to an active diagonal, eyeing the sensitive f7-square near Black’s king.

– Black does something similar with …Nc6 and …Bc5, developing pieces and fighting for central squares.

Now imagine that instead of 3…Bc5, Black plays 3…Nf6. Many players panic here because this was not the line they memorized. But the principles have not changed: you still want central control, development, and king safety. A move like 4.d3 or 4.Nc3 continues to follow these ideas and keeps your position healthy.

The more you understand why each move supports a principle, the less you depend on specific move orders. You start to see that openings are simply a way to reach middlegames you understand and enjoy.

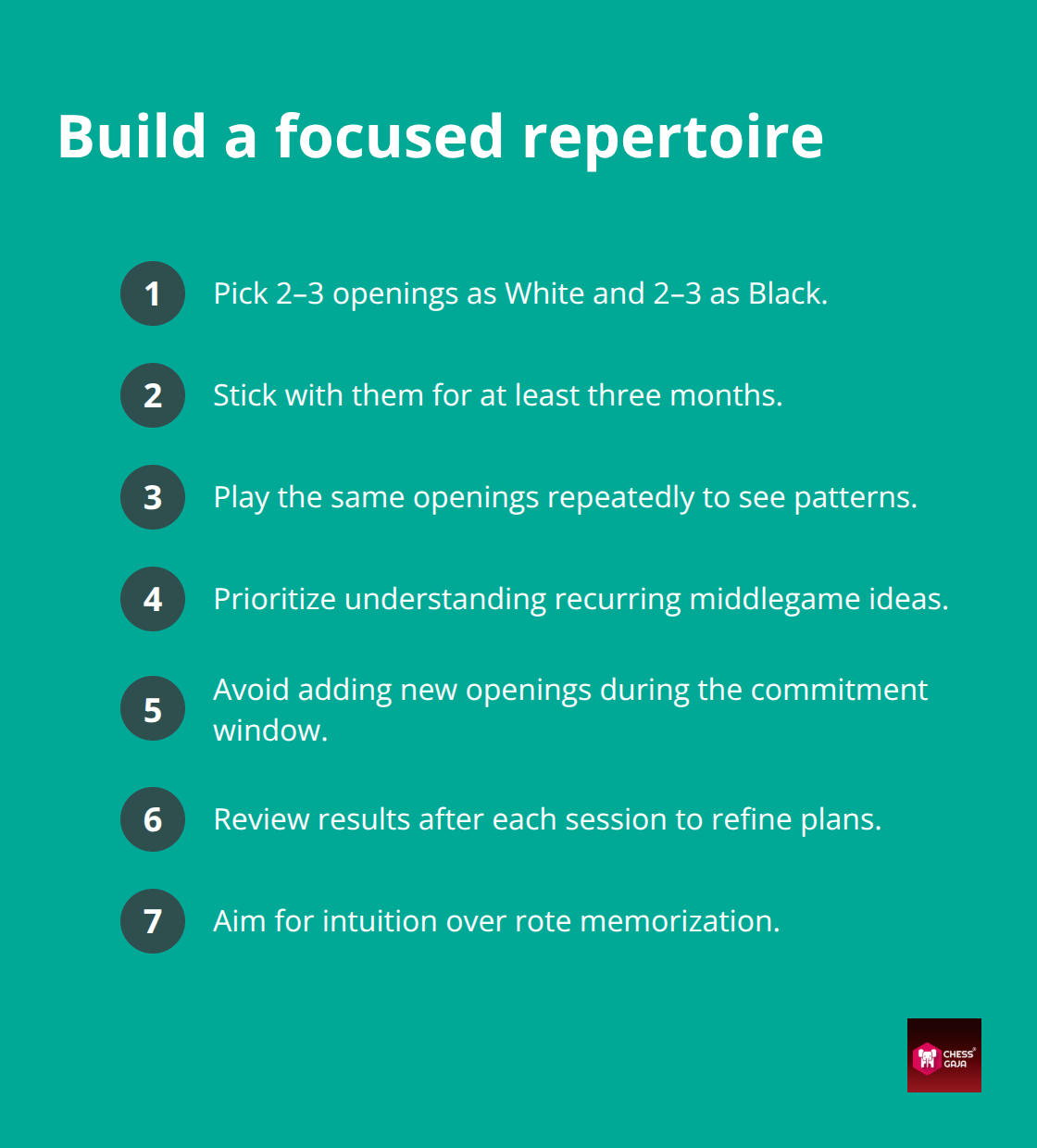

Building a Focused Opening Repertoire

A focused repertoire separates productive study from wasted effort. Many club players try to learn the Italian Game, the Sicilian, the French, and the Caro-Kann all at once, then wonder why nothing sticks.

For most players up to 1500, a better approach is:

– Choose 2 openings as White that lead to similar types of positions.

– Choose 2–3 defenses as Black, one against 1.e4 and one or two against 1.d4 (or other first moves).

– Commit to these choices for at least 3 months before switching.

When you play the same structures repeatedly, patterns start to jump out at you. You recognize where your knights belong, which pawn breaks are good, and what plans appear in the middlegame. That pattern recognition, not extra memorization, is what raises your playing strength.

Match Your Openings to Your Style

You will learn faster if your openings fit the type of middlegame you enjoy.

– If you like attacking the king and tactical positions, you might choose the Italian Game or Scotch Game as White and an active defense like the Sicilian as Black.

– If you prefer calmer, positional maneuvering, the Ruy Lopez or the Queen’s Gambit Declined-style structures may suit you better.

The key is not to pick the “objectively best” opening, but to pick systems where you want to understand the resulting middlegame. When your openings fit your style, your study feels natural instead of forced.

How to Practice Your Openings the Right Way

Choosing openings is only the beginning. Real improvement comes from how you practice them.

Analyze Your Own Games

After every serious game (online or over the board), spend at least 10–15 minutes reviewing the opening phase.

1. Write down the move where your opponent first deviated from what you expected.

2. Mark the move where you felt unsure or started “guessing.”

3. Ask: did I follow basic principles, or did I play random moves once I left my notes?

Often, you will notice that your position out of the opening was fine, but you did not understand the middlegame plans. That is a sign that you need to connect your opening moves to typical pawn breaks, piece placements, and attacks, not memorize more moves.

Practice Against Specific Problem Openings

If there is an opening that regularly gives you trouble, practice specifically against it.

– Struggling against the Caro-Kann as White? Play a training mini-match of 10 games where your opponent always plays 1…c6.

– Losing often to 1.d4 as Black? Find a training partner or use online tools to get many games in those structures.

Track your games in a simple spreadsheet: opening name, opponent rating, result, and one key moment where the game turned. After 20–30 games, patterns will emerge. You will see whether the problem is early in the opening or later in the middlegame.

Study Your Opponent’s Best Defenses

Another common mistake is only studying your own moves and ideas, ignoring how a strong opponent should defend.

For example, if you play the Italian Game as White, do not just learn your favorite attacking line. Also ask: what are Black’s most reliable responses, and what positions do they aim for?

Example 2: A typical Italian tactic – Nxf7

A classic idea for White in many Italian positions is the sacrifice on f7:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Nf6 4.Ng5 d5 5.exd5 Nxd5 6.Nxf7.

Here 6.Nxf7 is a tactical shot where the knight captures on f7, forking the queen and rook and dragging Black’s king into the open. This idea does not work in every position, but once you recognize the pattern, you will see it (and defend against it) in many similar structures.

By replaying 10–15 games where strong players defend against your favorite openings, you learn what good resistance looks like. Note where they place their pieces, which trades they accept, and which pawn breaks they play. This makes your preparation realistic instead of one-sided fantasy.

Common Opening Study Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake 1: Stopping Thinking When Theory Ends

Many players play confidently for the first 8–10 moves, then completely lose their way when the opponent plays something unexpected. They treat the opening like a script: once the prepared moves run out, they have no framework for making decisions.

Instead, the moment you are out of book, you should consciously switch to principle-based thinking:

– Which side has better development and king safety?

– Who controls the center and more space?

– What are the immediate threats for both sides?

If you simply apply these questions, you will often find strong moves even in completely new positions. Over time, this habit is worth more than any extra page of memorized theory.

Mistake 2: Ignoring the Opponent’s Plans

Some players study an opening as if they are playing against a passive opponent who never fights back. They only memorize “my plan,” not “our fight.”

Every time you review an opening, spend a few minutes asking: “If my opponent plays accurately, what position are they trying to reach?” Understanding both sides’ plans makes you much harder to surprise and helps you spot tactical resources for and against your ideas.

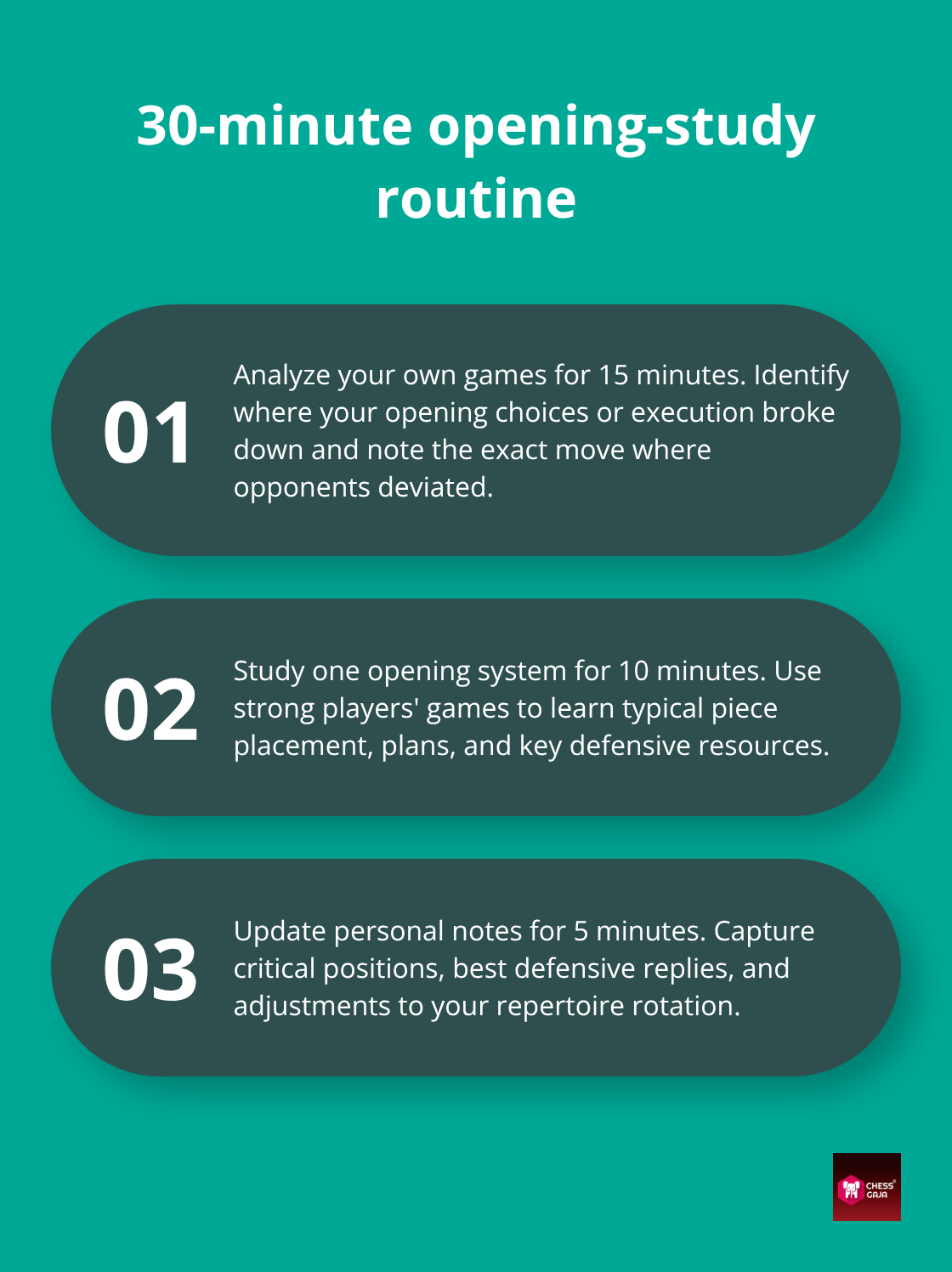

A Simple Weekly Opening Study Routine

You do not need hours of work every day to build a strong opening foundation. A realistic and sustainable plan for most players is three 30-minute sessions per week.

Here is a structure you can follow:

Session 1 (30 minutes): Analyze your own games

– 20 minutes: Review 1–2 recent games focusing only on the first 15 moves. Identify where your preparation ended and whether you still followed principles.

– 10 minutes: Note one key lesson about the structure or plan you reached.

Session 2 (30 minutes): Study model games

– 20 minutes: Play through one high-quality game in your chosen opening from a strong player, without an engine at first. Pause at critical moments and guess the next move.

– 10 minutes: Check with an engine or a database if you have access, and write down 1–2 typical ideas or pawn breaks you noticed.

Session 3 (30 minutes): Update notes and play training games

– 15 minutes: Update a simple repertoire file or notebook with key ideas, not long variations (for example: “Italian – common plan: d3, c3, Re1, followed by d4 pawn break”).

– 15 minutes: Play one or two focused training games online, specifically using your target opening, and save them for the next analysis session.

For the next 90 days, stick to the same small set of openings. By the end, you will recognize your structures instantly and feel far more comfortable when opponents deviate from your preparation.

Practice Tasks and Final Thoughts

To make this article actionable, here are concrete tasks you can start this week:

1. Define your mini-repertoire:

Choose 2 openings as White and 2–3 as Black that you will play for the next 90 days. Write down in one sentence what kind of middlegame position you want from each.

2. Create an opening notebook or file:

For each opening, write a short page with: main pawn structure, typical piece placement, and one common tactical idea (like Nxf7 in the Italian).

3. Analyze 5 recent games:

For each game, mark the move where you left your preparation and the first move you played without a clear idea. Ask whether you still followed basic principles at that moment.

4. Play a focused training set:

Pick one “problem opening” and play at least 10 games against it this month, recording the results and one key lesson from each game.

5. Study 5 model games:

Find 5 games by strong players in one of your main openings and replay them, pausing to ask what both sides are trying to achieve in the middlegame.

The next 90 days will transform how you approach opening study. When you commit to mastering a focused repertoire, analyzing your own games, and understanding middlegame plans rather than memorizing lines, your rating will improve measurably. You’ll recognize patterns others miss, think faster when opponents deviate, and make stronger decisions across the entire game.

Ready to accelerate your progress? Our FIDE-rated coaches at Chess Gaja specialize in building custom opening repertoires that match your playing style and rating level. Book a paid starter class session today to discover exactly which openings will serve your game best and how to practice them effectively for rapid improvement.