At Chess Gaja Academy, I’ve noticed the biggest difference between a club player and a professional is not how many lines they know, but how deeply they understand the ideas behind them. I’m Grandmaster Priyadharshan Kannappan, and “mastering” the opening means moving beyond memorization to gain full control over the resulting middlegame. In this article, I’ll share the pro-level habits—from analyzing pawn structures to preparing for specific opponents—that will help you start every game with the confidence of a seasoned expert.

The Three Rules That Fix Most Opening Mistakes

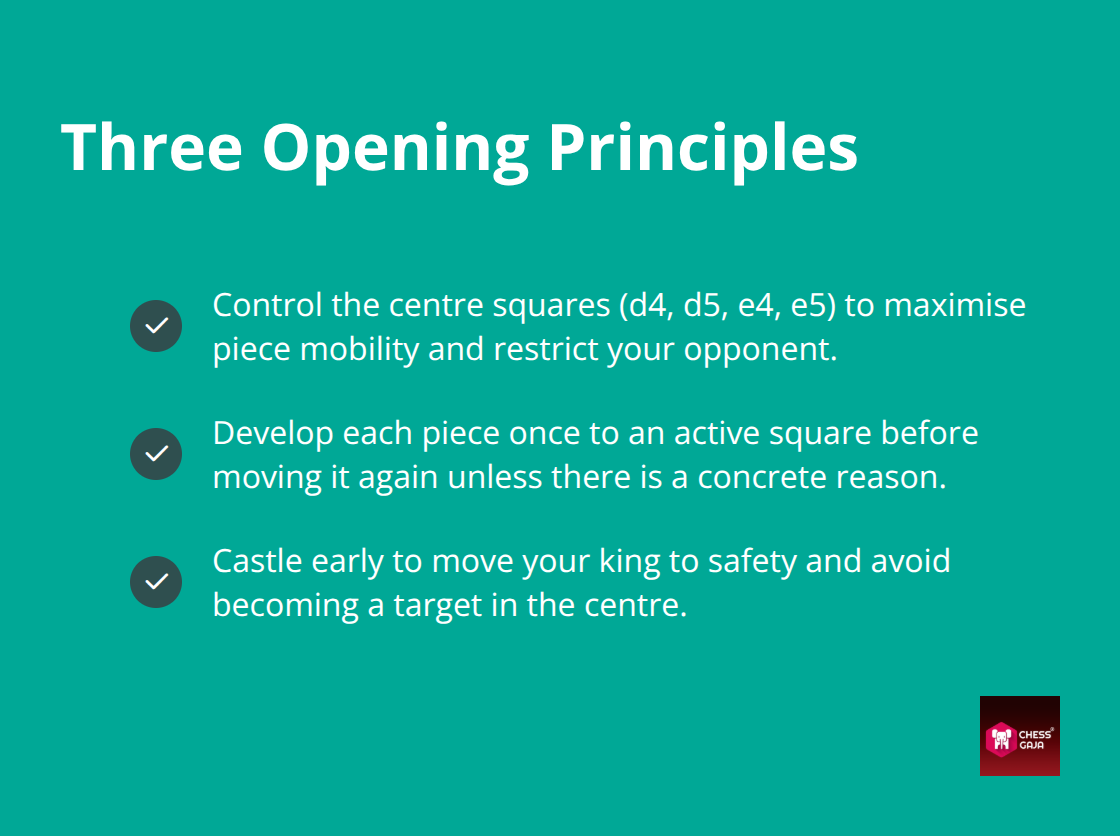

Your first 10 moves shape everything that comes after. Students waste months on 20-move opening lines, only to fall apart when opponents play something unexpected on move 7. The real power lies in three concrete principles that work in almost every opening: controlling the center squares (d4, d5, e4, e5), developing your pieces to active squares before moving the same piece twice, and keeping your king tucked away safely before the real battle begins. These aren’t suggestions-they’re the foundation that separates players who win from players who hope.

Why Center Control Wins Games at Your Level

When you play 1.e4 or 1.d4 as White, you fight for the four squares in the middle of the board because controlling them gives your pieces more mobility and restricts your opponent’s options. A player at 1500 rating who plays e4 and then develops a knight to f3, followed by a bishop to c4 or e2, controls more of the board than an opponent who moves pawns aimlessly to the edges. The Italian Game demonstrates this perfectly: after 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4, White has already claimed central influence with purpose. Black’s e5-pawn and White’s e4-pawn occupy the same critical space, and whoever develops pieces faster to support their center will dominate the position. This isn’t theory-it’s a practical advantage you can measure in your own games.

Develop Each Piece Once, Not Multiple Times

Most students at intermediate level move their queen or knight three or four times in the opening while other pieces remain on their starting squares. This costs you time and tempo. Your rook stays on a1 while you’ve already moved your queen to b3, then back to d1, then sideways to c2. Meanwhile, your opponent’s four pieces are already developed and attacking. The rule is simple: develop each piece one time to a square where it does something useful, then only move it again if there’s a concrete reason. A knight belongs on f3 or c3 for White because these squares control the center and support your pawn structure. A bishop on c4 or e2 controls key squares and prepares your king to castle. When you’ve developed your queen, both rooks, both bishops, and both knights-and your king is safe-then you can move pieces multiple times as part of your strategy. Count your piece moves in your next five games. Most players at 1500 rating move individual pieces 6–8 times before their opponent has moved pieces 4–5 times. That’s a losing habit.

Castle Your King to Safety Before You Attack

Castling exists for one reason: to move your king away from the center where it’s exposed. Beginners sometimes skip castling or delay it because they want to attack. This is wrong. If your king is still in the center on move 8 or 9, your opponent can sacrifice material just to keep it there, and you’ll struggle to defend. Castling kingside (after moving your f-pawn zero times and your h-pawn zero times) typically happens around move 8–10 for White and move 7–9 for Black. Getting your king to safety doesn’t mean you stop attacking-it means you attack from a position where your king isn’t a target. The French Defense shows this clearly: both sides form pawn chains in the center, but the player who castles first often dictates the middlegame because their king is secure while the opponent’s is still vulnerable.

What Happens When You Master These Three Rules

These three principles-center control, efficient piece development, and king safety-form the backbone of every strong opening. Once you apply them consistently, you’ll notice your positions feel more comfortable and your opponents struggle to create threats. The next step is to understand which specific openings fit your playing style and how to study them without wasting time on memorization.

Which Opening Should You Play Based on Your Style

The opening you choose matters less than understanding why you’re playing it. At 1500 rating, your playing style-whether you prefer solid positions, tactical complications, or flexible strategies-determines which openings will actually work for you. A defensive player who memorizes aggressive lines will struggle because the positions don’t match their instincts. Students gain 150+ rating points simply by switching to openings that suit how they naturally think. If you attack recklessly, you need an opening that gives you real attacking chances, not one that requires patient maneuvering. If you prefer solid structures, sharp theoretical battles will frustrate you.

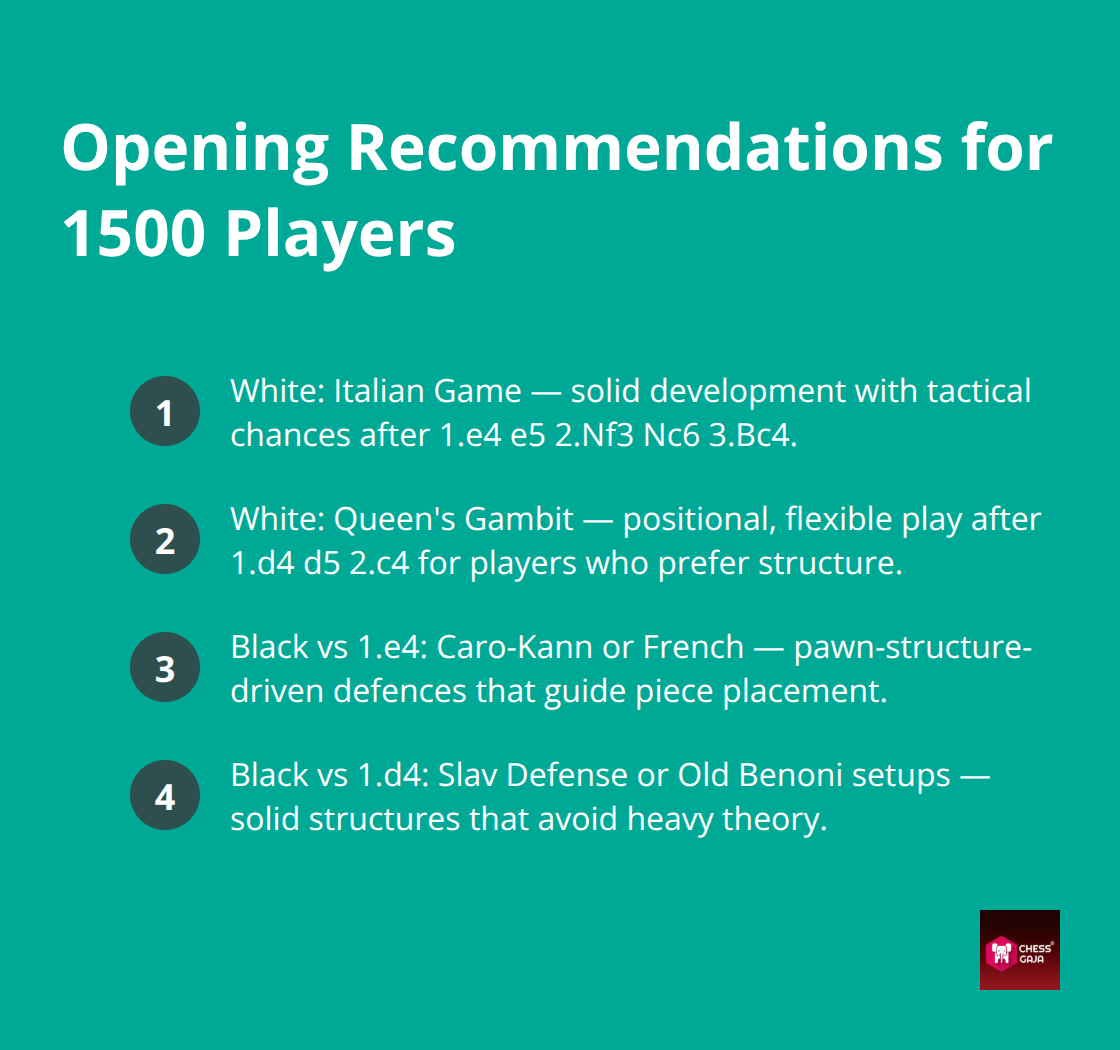

The Slav Defense works brilliantly for players who value structure and careful development. After 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6, Black has a pawn on d5 defended by another pawn on c6, creating a fortress-like setup. Your pieces develop naturally without awkward squares for your knights or bishops. Compare this to the Sicilian Defense, which Black plays after 1.e4 c5. The Sicilian creates immediate imbalance because Black trades a central pawn for White’s bishop pawn, leading to dynamic counterplay. If you enjoy tactics and don’t fear complications, the Sicilian gives you real winning chances at your level.

The Italian Game occupies the middle ground-it’s solid enough for defensive players yet offers enough tactical themes for aggressive players. After 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4, you control the center and develop purposefully, but the position can shift into tactics quickly if your opponent isn’t careful. For White, the Queen’s Gambit (1.d4 d5 2.c4) appeals to positional players because it offers flexibility. You can play for a small advantage through superior piece placement rather than forcing immediate tactics. Black can accept the gambit and fight for equality, or decline it and transpose into other structures. The key is this: your opening should feel natural when you play it, not like you follow a script you don’t understand. If your opponent’s moves constantly surprise you or you feel uncomfortable in the resulting positions, you’ve chosen an opening that doesn’t match your style.

Pick One Opening for Each Color and Master It First

Don’t learn six openings at once. Choose one solid opening as White and one as Black, then play them 20–30 times before adding anything else. This sounds slow, but strong players actually build their repertoire this way. When you’ve played the same opening repeatedly, you stop calculating the first 10 moves and instead think about your middlegame plans. Your brain frees up mental energy for strategy instead of memorization. Students who jump between openings every week memorize lines but never develop intuition. The students who improve fastest pick an opening, stick with it for two months, then expand only after they’ve played it successfully in real games.

For White at 1500 rating, the Italian Game or Queen’s Gambit are your best choices because both lead to positions where understanding beats memorization. For Black against 1.e4, the Caro-Kann Defense or French Defense create positions where the pawn structure guides your piece placement. You don’t need to memorize 30 variations, just understand where your pieces belong. Against 1.d4, the Slav Defense or the Old Benoni family (playing c5) give you solid structures without requiring theoretical knowledge. Once you’ve mastered these core openings, you can add a second weapon for variety, but not before.

Study Real Games Where Your Opening Appeared

After you’ve chosen your opening, find 5–10 games played by strong players in that exact opening and study them deeply. Don’t just watch the moves-pause after White’s 10th move and try to understand what White is trying to accomplish in the middlegame. What squares are important? Which pieces are the most active? Where will the real battle happen? This approach transforms opening study from memorization into pattern recognition. When you play your next game and reach move 12 in your chosen opening, you’ll recognize the middlegame structure because you’ve seen it before. You’ll know that your rooks belong on the d-file, or that your bishop should attack a particular square, because you studied how strong players handle the transition from opening to middlegame. This beats memorizing 20 moves every time.

The next step is to turn this knowledge into actual practice. Real games against opponents at your level will show you whether your opening choices truly work for you.

How to Study Openings Without Wasting Time on Memorization

The biggest mistake students make is treating opening study like vocabulary memorization. You sit with a chess board, write down move sequences, and repeat them until they stick in your head. Then you play a game, your opponent deviates on move 6, and suddenly you’re lost because you never learned the ideas behind those moves. Students who break through to 1700+ rating do something completely different. They study openings the way professional players do: they focus on understanding what each move accomplishes, then they test that understanding against real opponents. This approach takes less time and produces better results. A student who spends 30 minutes understanding why the bishop belongs on c4 in the Italian Game will perform better than a student who memorizes 20 moves in 90 minutes. The difference shows up immediately in your games.

Analyze Complete Games to Recognize Patterns

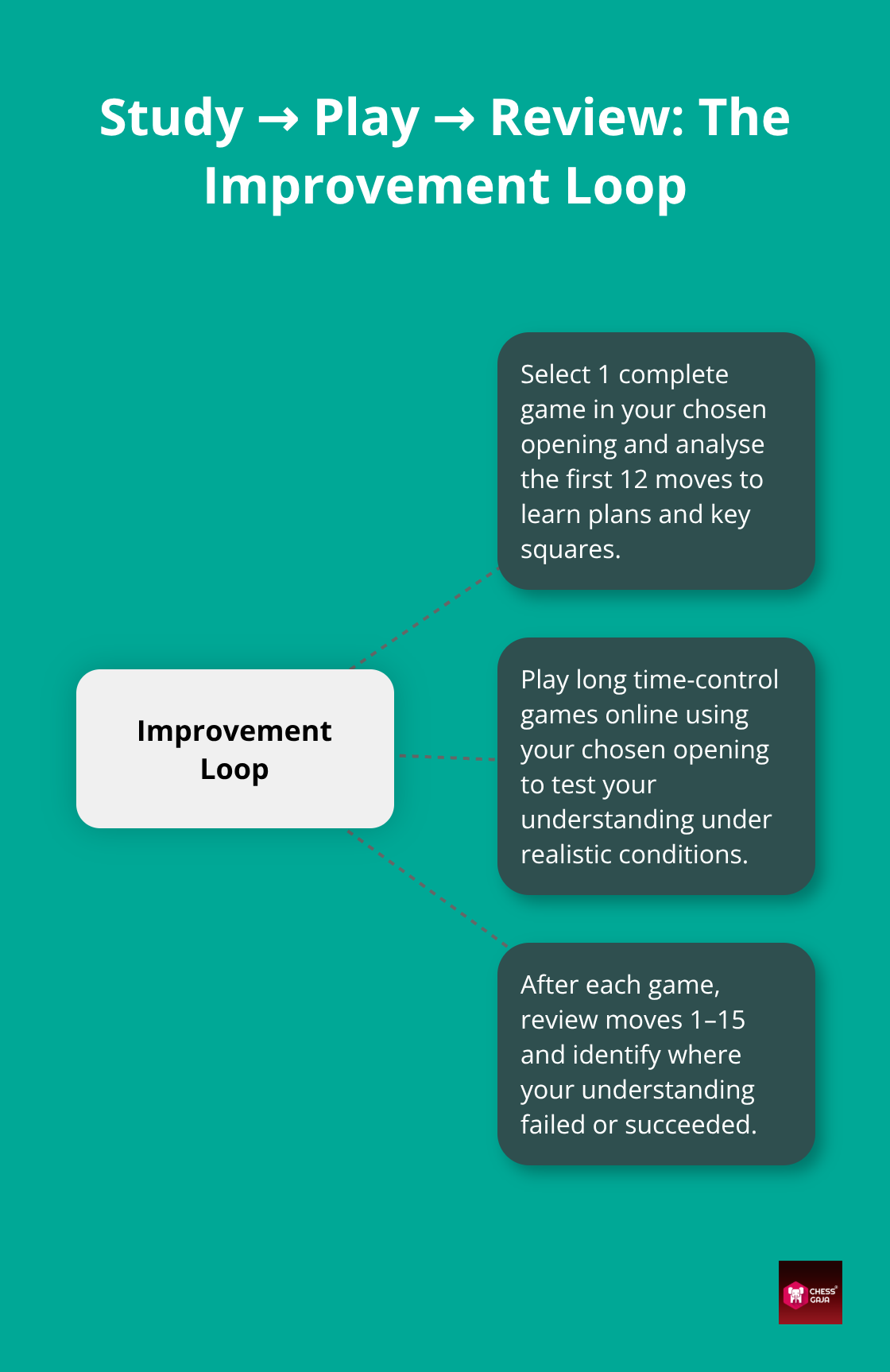

Start your opening study by selecting one complete game played by a strong player in your chosen opening, then stop the game after move 12 and analyze it yourself before looking ahead. Ask specific questions: why did White play e4 instead of d4? Why did Black develop the knight to f6 before playing d6? What squares matter most right now? What is White threatening, and how does Black defend? This active analysis forces your brain to connect moves to strategy instead of just memorizing sequences.

After you’ve analyzed those 12 moves, continue the game and compare your predictions to what actually happened. You’ll notice patterns emerge. In the Italian Game, White almost always plays for control of the d5 square. In the French Defense, Black’s light-squared bishop always struggles for activity, so Black’s strategy revolves around creating counterplay on the queenside or kingside to compensate. These patterns repeat across dozens of games, and once you recognize them, you don’t need to memorize variations anymore because you understand the direction the game naturally flows.

Play games online with long time controls and focus on opening principles. Your brain needs time to absorb the patterns. When you play your next tournament game in this opening, you’ll recognize the position after move 15 because your mind has seen similar structures before. This recognition beats memorization every single time.

Test Your Understanding in Real Games

Test your understanding in real games against players at your level. Online platforms like Chess.com offer rated games where you can play your chosen opening repeatedly and measure whether your preparation actually works. The critical step most students skip is reviewing those games afterward.

After every game you lose in your opening, spend 10 minutes analyzing moves 1–15 and identifying where your understanding broke down. Did your opponent play a move you didn’t expect? If so, was it a mistake, or does it represent a valid alternative you should learn about? Did you reach a position you recognized from your study, but then make a poor move in the middlegame? That tells you your opening knowledge was fine, but your middlegame planning needs work.

This feedback loop accelerates improvement dramatically. A student who plays 10 games and reviews each one learns more than a student who plays 30 games without analysis. The review process reveals whether your opening choices actually suit your playing style or whether you need to adjust.

Adjust Your Repertoire Based on Results

If you consistently reach positions where you feel uncomfortable despite winning the opening battle, your opening doesn’t match your instincts yet. Switch to a different system and try again. The goal isn’t to find the theoretically best opening; it’s to find the opening where you play naturally and confidently.

Once you’ve played your chosen opening 20–30 times in rated games and reviewed the results, you’ll know exactly which ideas work at your level and which ones don’t. That’s when you’re ready to expand your repertoire with a second opening or a new variation. The patterns you’ve learned from real games (not from memorized lines) will guide your decisions in positions you’ve never seen before.

Final Thoughts

Mastering the chess openings comes down to three concrete actions: understanding the principles behind your moves, choosing openings that match your playing style, and testing your knowledge in real games. The 12-year-old student we mentioned at the start of this article didn’t lose because he lacked talent-he lost because he memorized without thinking. Two months later, after switching to the Italian Game and studying five complete games from strong players, he won his next tournament.

Pick one opening as White and one as Black this week, then play them in 10 rated games online and review each game to identify patterns. Don’t add a second opening until you’ve played your first choice at least 20 times, since this focused approach builds intuition faster than jumping between six different systems. When you recognize a middlegame structure because you’ve seen it before, you’ll stop calculating and start playing with confidence.

We at Chess Gaja have guided hundreds of students through this exact process, and the results speak for themselves-students who commit to understanding openings rather than memorizing them typically gain 150–200 rating points within three months. Our FIDE-rated coaches provide personalized feedback on your opening choices and game analysis to help you identify which systems truly suit your style. Explore our group classes and private coaching options designed specifically for players at your level.