Last week, a student at Chess Gaja showed us their game where they missed three chances to win their opponent’s pieces in just ten moves. They knew something was wrong, but couldn’t see what.

The problem wasn’t that they lacked skill-it was that they hadn’t learned to recognize beginner chess tactics. Once you spot these patterns, winning material becomes straightforward.

At Chess Gaja Academy, I’ve seen many beginners get overwhelmed by complex variations when they should be focusing on the simple patterns that decide 90% of their games. I’m Grandmaster Priyadharshan Kannappan, and I believe that mastering tactics like forks, pins, and skewers is the fastest way to stop “hanging” pieces and start winning. In this guide, I strip away the complexity to show you how to spot these opportunities instantly, turning tactical vision from a struggle into a natural instinct.

The Fork: Your Fastest Way to Win Material

A fork happens when one piece attacks two or more opponent pieces at the same time, forcing them to lose material because they can only move one piece to safety. The knight is the most dangerous fork weapon because its L-shaped movement often surprises opponents and attacks pieces they thought were protected. In beginner games, forks win material in tactical sequences, which is why spotting them early transforms your results. The real power of a fork isn’t just winning a pawn-it’s that your opponent cannot defend both pieces simultaneously, making the outcome certain before they even move. This certainty is what separates forks from slower tactics: you don’t need to calculate ten moves ahead because the position decides itself in one move.

Where Forks Hide in Real Games

Most forks in beginner play follow predictable patterns that repeat across thousands of games. A knight jumps to the center of the board and often creates a fork on the king and queen, which happens so frequently that strong players automatically scan for this threat on every move. The f4 square is particularly dangerous for White because a knight there attacks both the king on e2 and the queen on d2 simultaneously-a position that appears in countless beginner games where White hasn’t castled early. Rooks and bishops create forks less often than knights, but they matter more when they do because the pieces they attack are usually further apart, making escape squares harder to find. In the opening phase, forks typically emerge around moves 8 to 15 when pieces are still underdeveloped and crowded together in vulnerable squares.

How to Train Your Fork Vision

The fastest way to spot forks is to ask one question after each opponent move: what two pieces are closest together and least protected? This single habit accelerates pattern recognition far more than memorizing fork positions.

You should solve 20 minutes of daily tactical puzzles that emphasize forks to build the neural pathways you need to spot them instantly in real games, and consistent daily practice beats occasional longer sessions. When you practice, focus on knight forks first because they’re the hardest to see but the most rewarding when you find them-once you master knight fork patterns, discovering bishop and rook forks becomes almost automatic. After you complete a puzzle, pause for five seconds and visualize where else that same fork pattern could appear on the board, which trains your mind to recognize variations rather than memorizing single positions.

What Comes Next: Building Your Tactical Arsenal

Forks form the foundation of tactical vision, but they represent only one piece of the puzzle. The pin-a tactic that paralyzes your opponent’s pieces and forces them into impossible choices-demands equal attention because it appears just as frequently in beginner games and often leads to even larger material gains.

The Pin: Paralyzing Your Opponent’s Pieces

A pin is a tactic where a piece is immobilized because moving it would expose a more valuable piece (often the king or queen) to capture. Unlike a fork, which forces an immediate loss, a pin paralyzes a piece and makes it nearly useless for the rest of the position. The pinned piece becomes a liability that cannot defend, cannot attack effectively, and cannot escape without losing material-this is why pins often decide beginner games before any tactical sequence even begins.

In beginner play around 1500 rating, pins appear frequently because uncastled kings and crowded piece placements create the exact conditions pins need to thrive. The bishop stands as the most common pinning piece because its long-range diagonal control stretches across the entire board, and many beginners fail to notice when their pieces are pinned until they move and lose material. A pin on the e-file against an uncastled king is devastatingly common-White’s bishop on e5 pins Black’s queen to the king on e8 in thousands of games where Black hasn’t castled by move 10.

The real advantage of a pin isn’t just winning material; it’s that your opponent’s best-placed piece becomes frozen, which gives you time to improve your own position, launch an attack elsewhere on the board, or simply consolidate a material advantage. After each move, ask yourself this question: which of my pieces could I move to pin one of my opponent’s pieces to their king, queen, or rook? This single habit transforms pins from invisible tactics into obvious winning moves.

Spotting Pins Before Your Opponent Does

Most beginners miss pins because they focus only on immediate threats rather than scanning for pieces that sit on the same file, rank, or diagonal as more valuable pieces. The most dangerous pins occur on the long diagonal (a1 to h8) and the e-file because these lines naturally pass through both the king and queen in typical opening positions.

Train yourself to identify pins by working backward: first locate your opponent’s king, then trace every line extending from that king and ask whether any of your pieces sit on that line with an opponent piece in between. Rooks create powerful pins on files and ranks, particularly the e-file and d-file in the opening, and a rook pin often wins material within three to five moves because the pinned piece cannot escape.

The difference between a pin and a fork matters greatly-a fork creates two simultaneous threats so your opponent must choose which piece to lose, while a pin creates only one threat but makes that threat inescapable because moving the pinned piece loses more material than staying put. Solve tactical puzzles that feature pins daily, and focus specifically on positions where the pinned piece is a queen or rook rather than a minor piece, because pins against high-value pieces yield larger material gains and appear more frequently in real games.

After you complete each pin puzzle, identify whether the pin was created by a bishop, rook, or queen, then visualize three other board positions where the same piece could create the same type of pin-this mental exercise accelerates your ability to recognize pins in positions that differ from the original puzzle.

Why Pin Recognition Changes Your Results Immediately

A student recently reviewed their games and discovered they had missed seven pinning opportunities in just five games, losing rating points they could have won. Once they spent one week focusing on pin recognition drills, their next ten games showed dramatic improvement because they began seeing pins automatically without conscious calculation.

The speed at which pins appear in beginner games means that improving your pin recognition typically raises your rating within weeks of focused practice. The psychological advantage of pinning is equally important-once your opponent realizes their piece is pinned, they often play passively or make desperate moves trying to escape the pin, which gives you the initiative to dictate the game’s direction.

Strong players at 2000+ rating spend minimal time thinking about pins because they recognize them instantly. This is the skill level you build toward through daily puzzle practice and real-game analysis. Yet pins represent only half of the paralyzing tactics that dominate beginner chess-skewers and discovered attacks operate on similar principles but demand different recognition skills, and mastering all three tactics creates an unstoppable tactical foundation.

Skewers and Discovered Attacks: Forcing Wins

A skewer is the reverse of a pin-instead of a valuable piece sitting behind a less valuable one, the valuable piece stands in front and must move, exposing the weaker piece behind it to capture. Beginners often confuse skewers with pins because both tactics immobilize pieces, but the key difference determines whether you win material immediately or gradually. When White’s queen moves to h8 with check against Black’s king, the king must escape, and the rook behind it falls to White’s queen on the next move-this is a skewer, and it forces an immediate material loss that the opponent cannot prevent.

The reason skewers devastate beginners is that they appear in endgames and middlegames where high-value pieces naturally cluster together, and the forcing nature of the check or attack leaves no room for defense. You spot skewers by asking this question after each move: can I attack my opponent’s strongest piece in a way that forces it to move and exposes a weaker piece directly behind it? This single habit catches skewers and discovered attacks that most beginners miss because they focus only on the attacked piece rather than scanning for targets behind it.

How Discovered Attacks Create Double Threats

Discovered attacks operate on a different principle-when you move your own piece, it uncovers an attack from another piece that was hidden behind it, creating two threats simultaneously. A bishop on e1 that has been blocked by your knight on d2 suddenly attacks the opponent’s queen when you move that knight elsewhere, and if the knight also creates its own threat, your opponent faces an impossible choice. The power of a discovered attack lies in its surprise element-your opponent sees one piece moving and fails to notice that an entirely different piece now attacks them, which means you often win material before they even recognize the danger.

In games between 1400 and 1600 rated players, discovered attacks win material in tactical positions because beginners habitually overlook threats from pieces that weren’t directly involved in the last move. To train discovered attack recognition, solve puzzles where moving a piece reveals a bishop or rook attack on the opponent’s queen, then pause and identify which piece created the discovered attack and which piece was hidden. This mental separation prevents the confusion that causes beginners to miss these tactics in real games.

Preventing Skewers and Discovered Attacks Before They Strike

The fastest way to defend against skewers and discovered attacks is to prevent them before they happen. After your opponent moves, scan your position for pieces that sit directly behind your most valuable pieces on the same file, rank, or diagonal-if an opponent piece occupies that square, you have a potential skewer waiting to happen. Similarly, identify which of your opponent’s pieces are blocked by their own pieces on long diagonals or open files, because moving the blocking piece creates a discovered attack.

Strong players at 1700 rating spend ten seconds after each opponent move asking these two questions, which is why they rarely fall victim to these tactics. You develop this habit through daily analysis of your own games, not just puzzle solving-when you lose material to a skewer or discovered attack, write down the position before the tactic occurred and study why you failed to prevent it.

Building Pattern Recognition Through Mixed Tactical Training

Solve fifteen puzzles daily that combine skewers, discovered attacks, and pins in random order, which forces your brain to distinguish between these three tactics under time pressure. The reason this mixed approach works better than studying each tactic separately is that real games never announce which tactic is coming-your opponent creates whichever tactic the position allows, and you must recognize it instantly. After solving each puzzle, note whether the solution involved a skewer, discovered attack, or pin, then identify the key square or piece that made the tactic possible.

Within three weeks of consistent practice, you will notice that these tactics begin to appear obvious in your games because your pattern recognition has accelerated dramatically. The mental effort you invest in distinguishing between these three related tactics pays dividends across your entire game, not just in tactical positions.

Final Thoughts

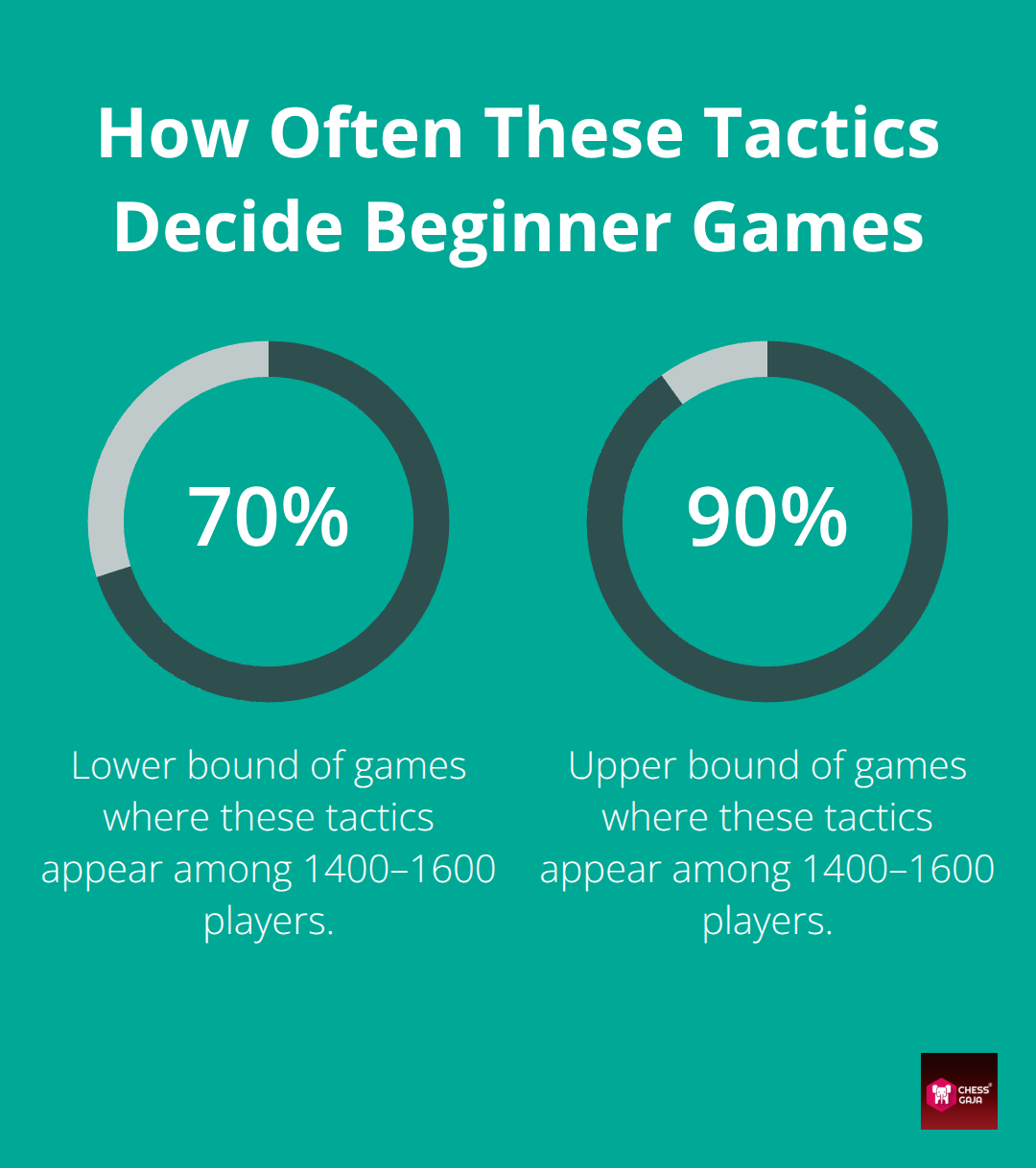

You now understand the three tactics that decide most beginner chess games: forks win material through simultaneous attacks, pins paralyze pieces by threatening more valuable targets, and skewers force high-value pieces to move and expose weaker ones behind them. These three patterns appear in roughly 70 to 90 percent of games between 1400 and 1600 rated players, which means mastering them transforms your results faster than studying openings or endgames.

The path forward requires one habit: spend twenty minutes daily solving tactical puzzles that mix all three patterns together, which trains your brain to recognize them under the time pressure of real games.

Within four weeks of consistent practice, you will notice these tactics appearing obvious in positions where you previously saw nothing. A student who solves puzzles for twenty minutes every single day gains roughly forty to sixty rating points within two months, while a student who practices sporadically gains almost nothing. The consistency matters far more than the duration, and your rating typically climbs ten to twenty points per week once pattern recognition becomes automatic.

Your next step is to commit to one week of focused practice on forks alone, then one week on pins, then one week on skewers and discovered attacks. If you want personalized guidance on which beginner chess tactics to prioritize based on your specific weaknesses, we at Chess Gaja offer coaching from FIDE-rated instructors who analyze your games and create customized training plans that accelerate your improvement. The combination of daily puzzle practice and expert feedback creates the fastest path to mastering these fundamental tactics and building a strong foundation for advanced play.